Home →

Compressions

Pressure Release Study, Part II

by Tom Brown, Jr.

In the last issue, we concerned ourselves with a study of the major pressure releases

of changing forward motion and foot mapping. In this issue, we will concentrate on

pressures against the wall (see Figure 1), which tell how much pressure is exerted on any

side, front, or rear of a track. The wall is that part of the track which is formed when

the print is placed in the ground, extending from the ground level to the bottom of the

track.

Understanding the wall pressure release systems will help you determine how much

pressure is placed on the wall, thereby indicating turning, pivoting, sliding, and so many

other nuances that are found in each individual track. Keep in mind that I am only

covering the major pressure releases and many points are left out in between. These points

will become evident when you have put in a few thousand hours of dirt time and are looking

for much finer detail. Also, keep in mind, no matter what the soil, these same pressure

releases occur in the same order. Of course, on hard dirt you will need a magnifying glass

to read the dirt particles that will lay in the ways to be mentioned.

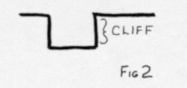

Cliff (see figure 2)

Any time a print goes straight in and out, a wall, or cliff will occur. This indicates

that there is no pressure against the wall. The cliff is usually at a 90 degree angle from

the ground level to the bottom of the track. |

|

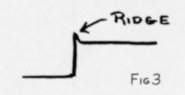

Ridge (see figure 3)

As pressure is placed against the wall, a small ridge is formed at the ground level that

will continue along the outside of the track until the point where the pressure stops. The

greatest point of pressure on ridges are marked by peaks. These peaks are very important

in determine indicator pressure releases and the exact points of pressure determine subtle

changes in movement. |

|

Crest (see figure 4)

As the pressure increases against the wall, the ridge is built higher and the dirt

begins to crest backwards over the foot.

Remember that this pressure release will still stay intact when the foot is removed

-because the foot restricts and is pulled out evenly. Any more pressure beyond a crest

will result in what is known as a cave or caving (see Figure 5), then continuing on to a

cave-in (See Figure 6). Keep in mind that weathering will crumble a crest and it could be

misread by an inexperienced tracker.

| Plate (see figure 7) With extreme pressure now against the wall, a huge plate is thrown up. The whole wall

rides up and above the ground level resulting in a plating effect. A number of these

plates can occur at the same time, the largest ones being the area of greatest pressure.

|

|

Plate Fissure (see figure 8)

Even more pressure now causes the plate to throw long cracks called fissures. Keep in

mind, any time the term "crack" is used alone it means that the dirt has cracked

or broken due to weath ring and not to stress; fissures refer toe stress. If the pressure

continues, then the plate crumbles, showing even greater pressure and stress against the

wall (See, Figure 9).

| |

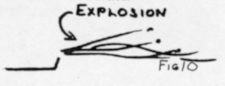

| Explosion (See Figure 10) An explosion is the greatest amount of pressure and stress any wall can stand and

usually means that the wall is completely blown out. This usually takes a very violent

motion, and the stress can be judged by the amount of dirt kicked out of the track and the

distance it has traveled.

|

|

Practicing Pressure Releases

All dirt moves in the same way with few exceptions, but all types

have their own quirks, depending on consistency, moisture, and composition. Fortunately,

these will not affect the major pressure releases listed, but only those minute ones that

take much time and study to learn. By the time you get to that point, you know most dirt

very well and are aware of the little inconsistencies of the soil you are working with.

To practice pressure releases, it is best to find a damp, sandy beach; being an ocean,

lake, or stream will make little difference. Usually, these areas are littered with tracks

of men and animals, but it is a good idea to wipe the slate clean and make your own.

Practice the various speed variations and changes you learned in the last newsletter, then

various turns and pivots. Pick out the pressure releases you see in the illustrations.

This way when you make the track you know exactly what you were doing, how fast you were

going, and to what degree you turned.

Later, as your skill increases, go for the other human tracks you find, then to the

animals. Don't graduate to different dirt until you can master the releases in simple sand

situations. Then, slowly bring your skill up by trying more and more difficult dirt until

you can see the pressure releases in hard-packed earth in the form of dust particle

pilings.

As you get more advanced, you will discover how each digit and portion of a finger or

toe can have its own set of pressure releases differing from others on the same foot. This

and other advanced methods will be covered in future articles along with some of the more

isolated releases and pivots common to all tracks.

Many of you have written to me about the foot mapping portion of the last article and

how you thought it could be done better. You are right, providing that is all there is to

pressure releases. But, unfortunately, there is so much more, and only that system will

work for the more advanced methods and especially correlate to the depth foot mapping that

we will discuss in later issues. So please use this method. You'll soon see why it is the

only way that will work.

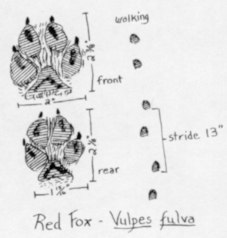

| Note Some people have asked how it would be

possible to map a small foot such as a rodent's forepaw. Simply draw to scale, saying that

one inch equals one foot, then draw in the pressure releases on the foot map. A magnifying

glass is helpful in reading mice and other small animal pressure releases. |

|

From The Tracker magazine,

1984,

published by the Tracker School.

For more articles from The Tracker magazine, visit the

Tracker Trail website.

|